On the 1st of October, it will be six months since Guide Dog Sienna entered my life! To mark the occasion, I will write a series of posts over the next few weeks explaining the difference working with a guide dog has made for me.

It seems like a lifetime ago that Guide Dog Sienna arrived at my house. In reality, it was 1 April 2022 and we promptly began our training the next day. At the end of the training, we were released into the world and that is where much of the learning began!

The most significant change I have noticed is that I am more confident when out and about in unfamiliar environments. Working with Sienna has considerably decreased the fatigue associated with navigating the environment with deteriorating vision.

I will describe an example. I had not noticed that I had unconsciously stopped going out as much and was experiencing extreme fatigue due to vision changes and associated cognitive load with getting around my environment.

One particular instance where this was particularly challenging was after I got a new hearing aid and had a professional event after work with a health informatics organisation I support (about a year ago) in a part of town I was unfamiliar with.

I did my usual preparation with bus routes and arranged to call a friend to get me when I arrived at a local Pub as I was worried I would not be able to see her in a crowd so we could walk the rest of the way together. This journey meant walking through the city at dusk during rush hour. I had lost about 30 degrees of my central vision over the preceding six months and was pushing myself to keep engaging in my professional responsibilities.

I was walking up Victoria St in Auckland, there was rush hour traffic, many people bustling and dreaded road works that made the route different to what I expected. The sun was going down and reflecting of a building making it very difficult to see anything. I was using my cane but because of the new hearing aid and vision loss the visual and audible stimulation this situation became overwhelming. So much so that I needed to stop, sit on a nearby bollard and close my eyes to recover a little.

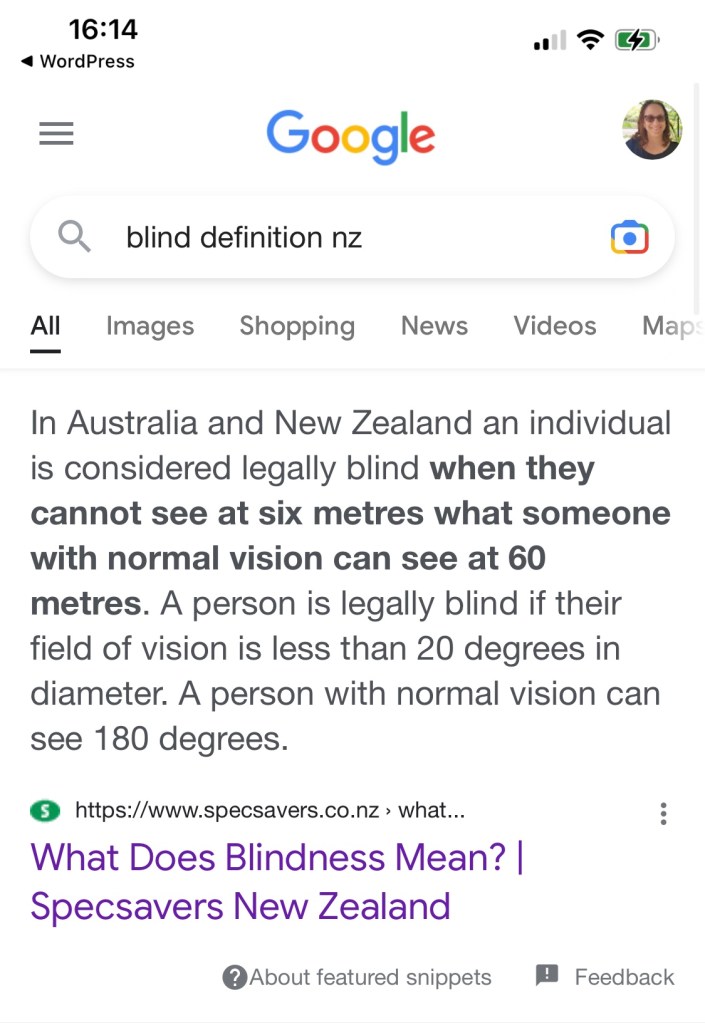

To give more context, I had about 20 degrees of vision on my left lateral side (now I have about 5-10 degrees). In this area, my vision is patchy and my brain fills in the gaps in vision that the blind spots obscure. When I am tired or in fast-moving crowds, my brain stops being able to fill in the gaps. This causes distortion, nausea and dizziness.

After five or so minutes, I continued up the road to the Pub, texted my friend and I waited for around 10 minutes. I followed this up with a phone call which went to answer phone. By this time, the street was even more crowded, so I went into the pub to look for them. There were four large areas. I scouted around all of these, hoping that one of the groups would recognise me or I would recognise one of their voices.

Unfortunately, I didn’t recognise anyone and no one called out. I went back outside where I had arranged to meet my friend and called again, getting her answer phone. By this time, the visual distortion from the crowd and traffic made me nauseous, dizzy. and emotionally drained. I was already tired from a typical work day, so I decided it would be best to go home and skip the awards dispute wanting to go. I left my friend a message saying I would get something to eat and head home because I couldn’t find the group.

I retraced my steps, realising I would need to walk some distance to get the bus home, so I stopped at a small cafe to get a cup of tea. My friend called me as I finished my tea, saying her phone was in her bag and she got my message. We agreed she would wait outside the pub. I decided to join the group and returned to the Pub.

With the fatigue associated with getting there, I found interacting with the group in a noisy social environment almost impossible and had run out of energy. In hindsight, this may have been an excellent opportunity to listen to my body and go home to rest.

However, I chose to push on my goal had been to reengage with professional obligations, colleagues and industry. We walked as a group down to the company hosting the event.

Awards were given, and food and drink were shared, but I was so exhausted I couldn’t engage at the level I usually would have. I was lucky my friend noticed and arranged a lift home for me with a colleague, as the travel to the event had left me physically and emotionally exhausted.

I had applied for a guide dog about eight months before this occurred, thinking that it would be something that would be useful later in my life. I had heard that the wait time was 2-6 years and that getting a guide dog was something of the future. It was after this that I realised that perhaps working with a guide dog was something I needed at that time rather than in the future.

If I contrast this with similar events now with Guide Dog Sienna, the difference is immense. Last week we went to Wellington to a Digital Health Leadership Summit, which was all city centre, unfamiliar routes and many people and moving objects. However, having Sienna there decreased my visual fatigue and cognitive load as she helped me avoid people and objects as opposed to locating and navigating them with a white cane and vision. This means I don’t need to use my remaining vision or interpret tactile feedback and is the difference between participating fully or in a limited fashion.

While I didn’t attend one function, this wasn’t related to my vision or fatigue but redundancy notices at my work that I wanted some downtime to process that announcement.

So the conclusion of my first post about the difference that Sienna has made is that she has allowed me to function with less cognitive load and visual fatigue in my job.

I can’t end a blog post without some Sienna cuteness.